A transdisciplinary project that reflects on the prospects of a sustainable economic development respectful of natural resources, in response to the challenges of the Anthropocene.

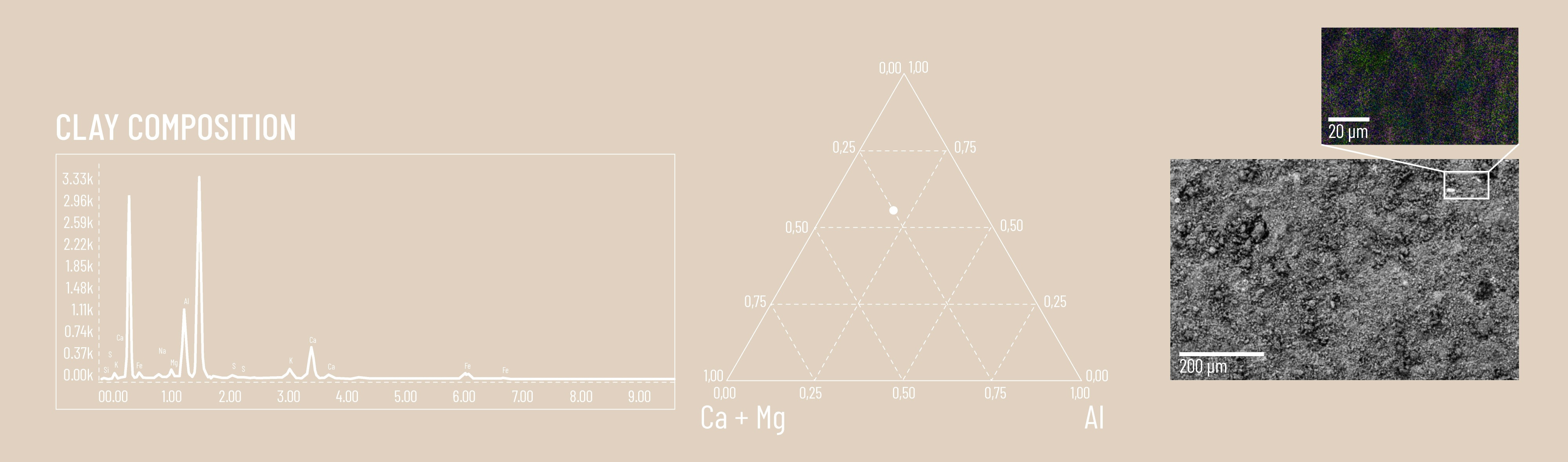

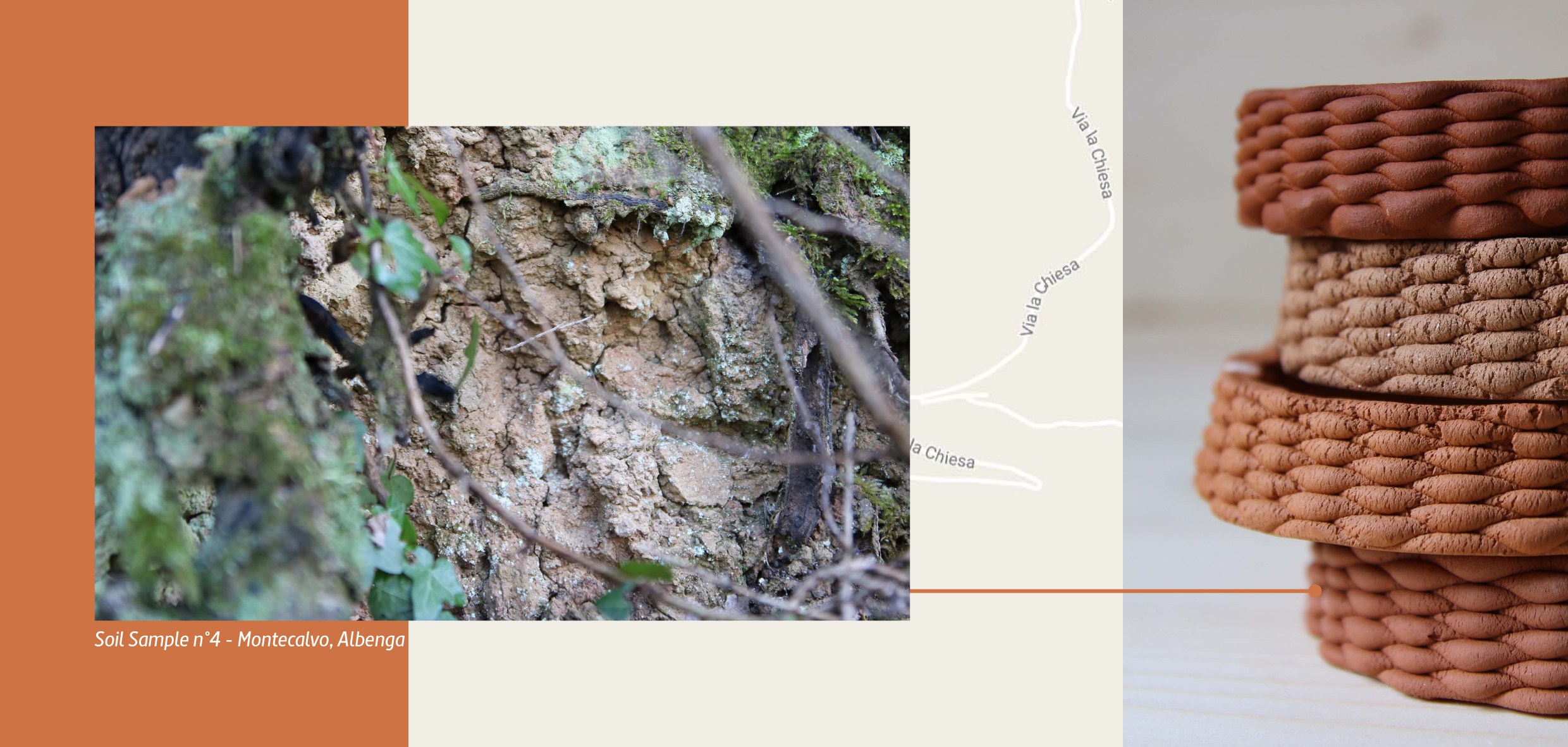

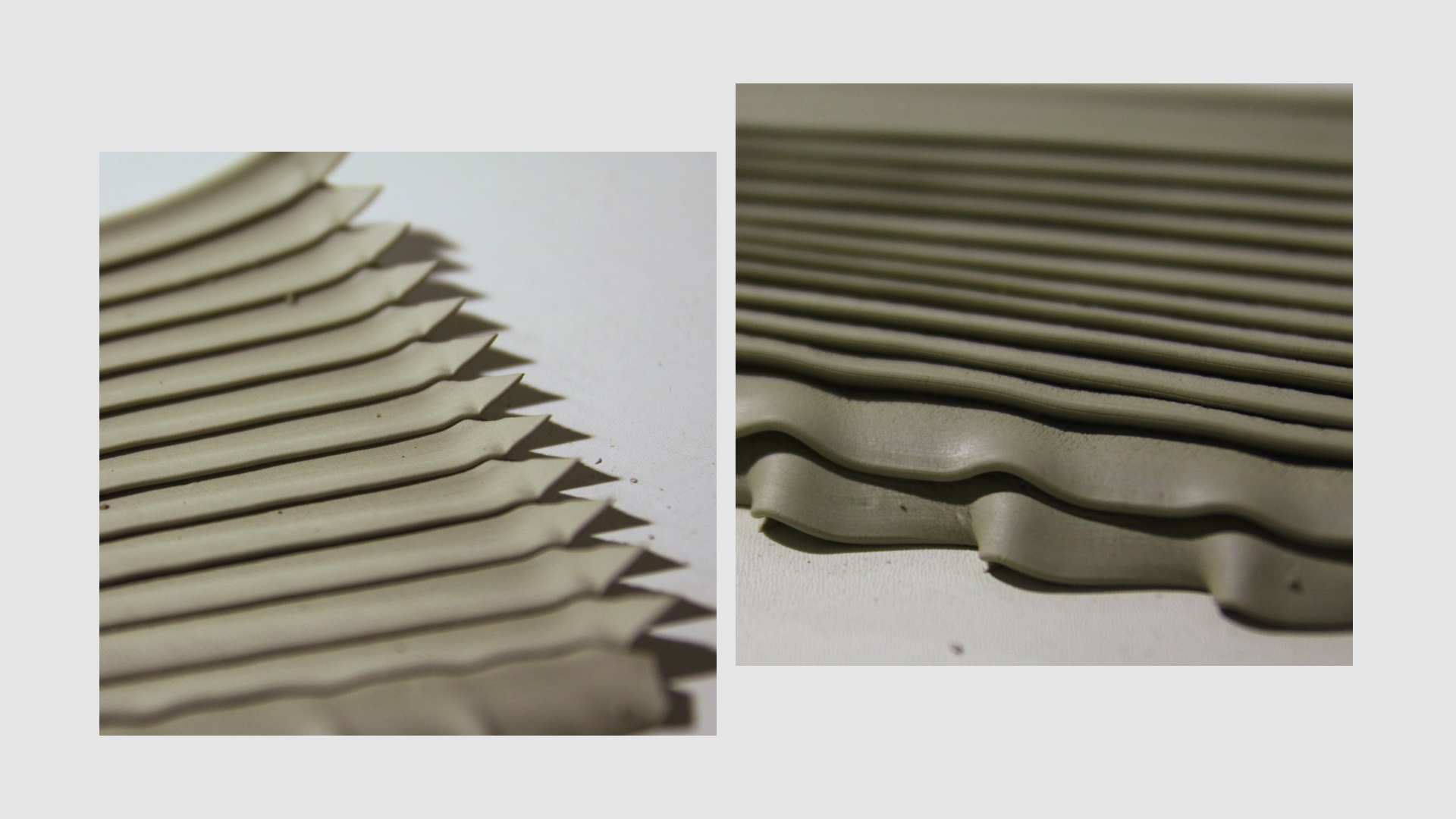

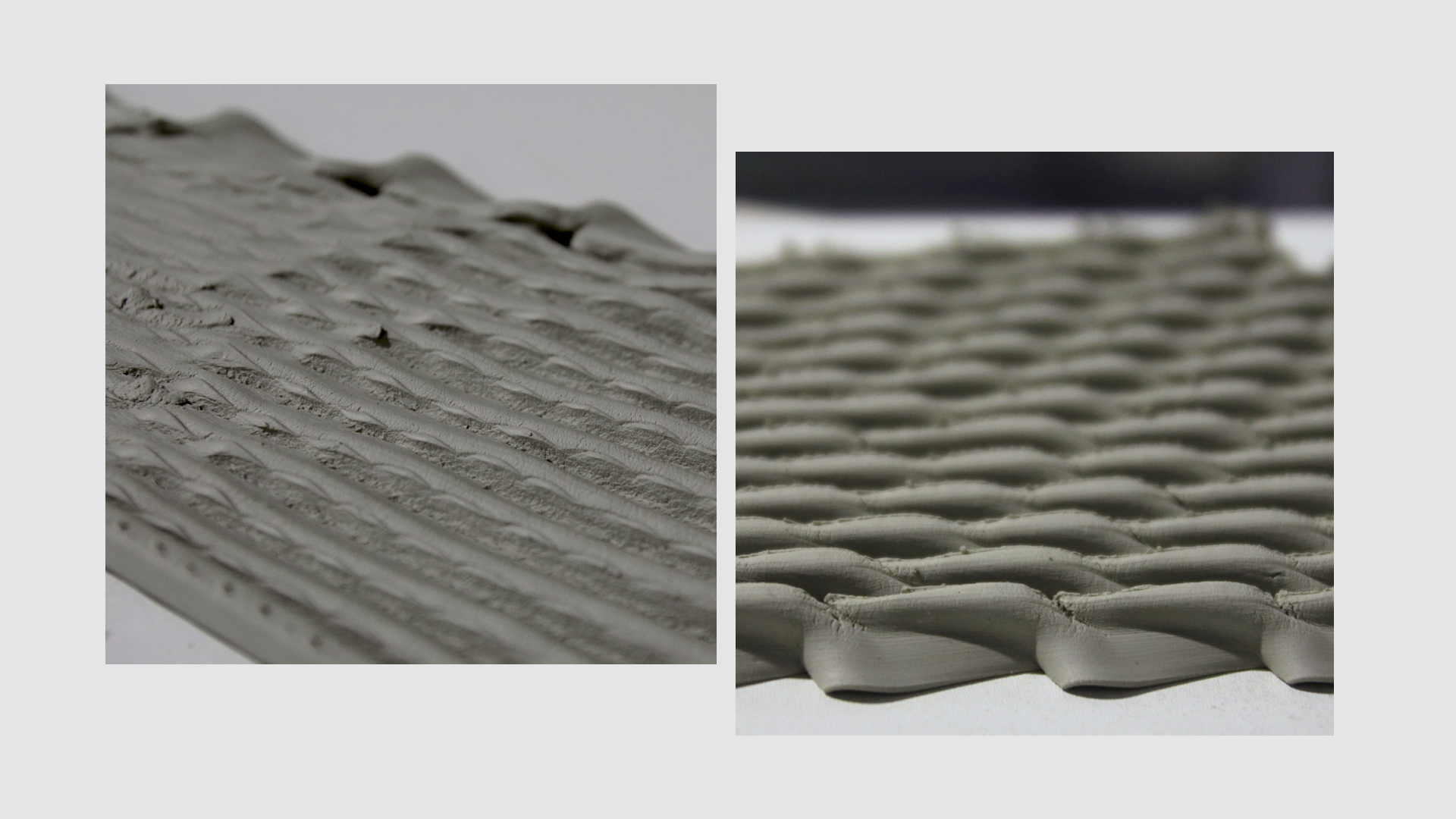

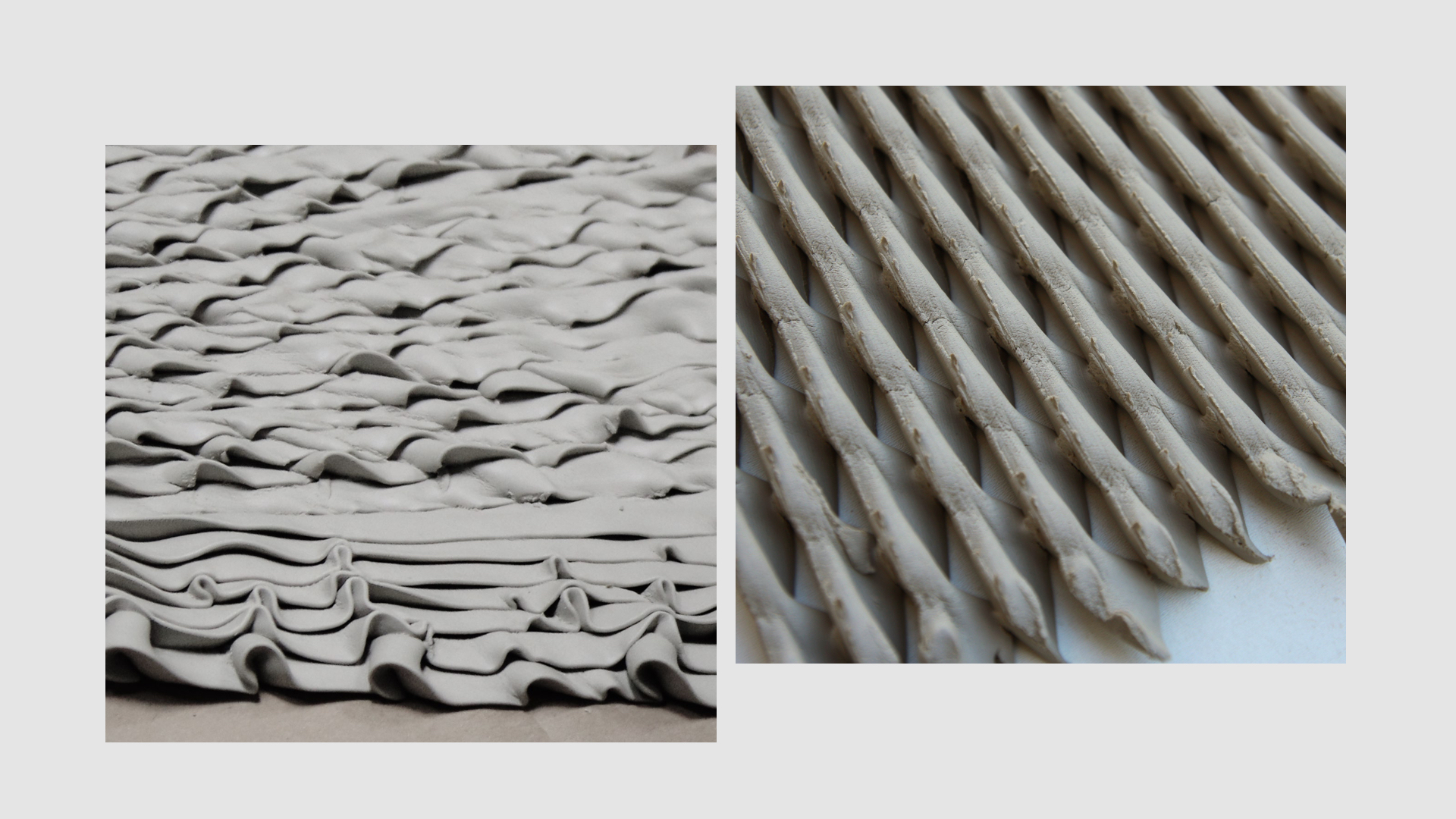

It promotes a new, localised approach to innovation: rooted in the rediscovery and appreciation of territorial material resources, shaped by the integration of hyper-local crafts know-how with distributed digital technologies.

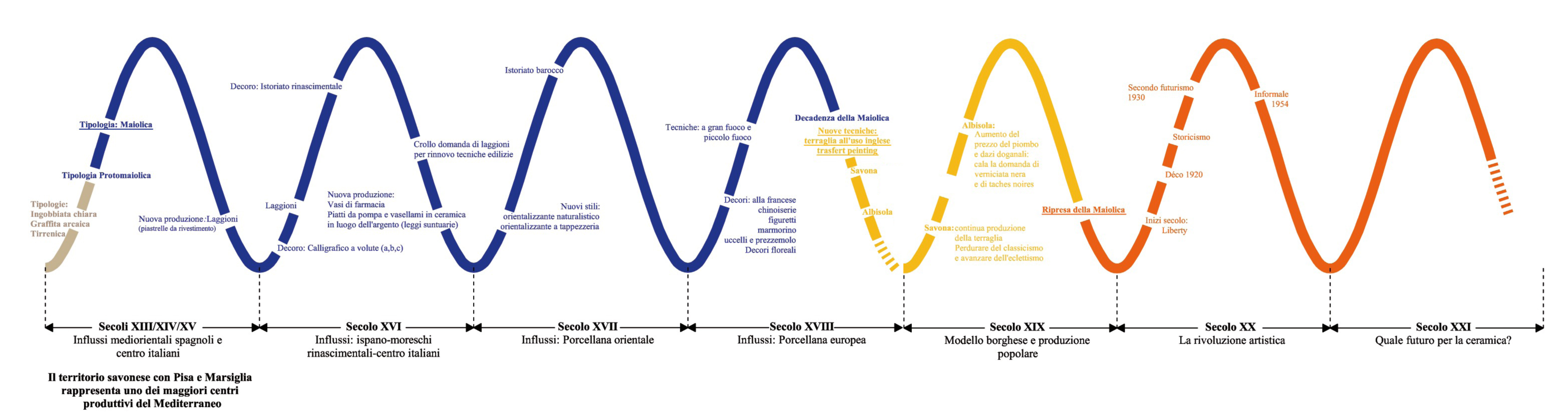

Ceramics for the Anthropocene is the result of a collaboration with the local community of italian ceramicists based in the area of Albisola Superiore, the Engineering Department of the University of Genova and the DigifabTURINg robotic fabrication research lab based at the Fablab Torino. It was developed during the residency program BE sm/ART 2 organised by Radicate.eu.